This is the first in a series of special articles we’ll be featuring over the coming weeks about the opioid crisis facing Canada and the United States. Opioid-related addiction is overwhelming millions of people, and the number of fatal overdoses has eclipsed loss of life due to guns or breast cancer. One North Carolina church calls addiction by name every Sunday, and even used a portion of its Easter services to specifically address this crisis.

“So if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed.”

—John 8:36

“You’ve got 10 minutes,” Derek Jenkins told the pastor as he stepped into his small Eastern North Carolina house church.

Hmmm. Ten minutes for what?

Pastor Donnie Griggs distinctly remembers Jenkins was on edge that Sunday morning. He carried a “say what you need to say attitude,” but Griggs knew it would take longer than 10 minutes to convince him of anything — especially that God loved him and had a plan for his life.

But soon, the pastor realized that Jenkins wasn’t keeping track, and carried on with what was just the second Sunday service at the start-up church, One Harbor.

Jenkins was too busy talking on his phone, nervously pacing around the Morehead City living room where a dozen or so people sat trying to hear Griggs’ Sunday morning sermon.

“Something in me just decided to let it be,” Griggs remembered about Jenkins’ rough introduction and inattention. “It wasn’t until weeks later I realized he was on his way to end his life.”

LSD, grilled cheese & a downward spiral

The Jenkins that walked into that house church was miserable, agitated. And sober.

“I really honestly was just done,” Jenkins said. “The only time I’d ever been really considering dying was when I was sober. When I was doing drugs, I was loving it.”

At first, drugs offered more than an escape. They were lucrative. The product of a troubled home, Jenkins as a teenager got a fake Grateful Dead ticket and hitchhiked to the concert.

“I found out real quick I could make money selling LSD and grilled cheese,” he said.

His business model stayed the same for years until singer-guitarist Jerry Garcia died in 1995. Jenkins decided to hang it up and see what tomorrow would bring. He headed back to his beach home to find a job and try his hand at a family.

But marriage was hard. And being a dad was hard. Using drugs was easy. When he discovered heroin, an illegal and very addicting opioid, he said he found a relief unlike anything else he had ever known. He was up to 20 bags a day by the time he got busted a little more than a decade ago.

How Your Church Can Join the Opioid Fight:

Last year, nearly 4,000 people in Canada died from overdosing on opioids, which include prescription painkillers like oxycodone or illegal street drugs fentanyl and heroin. North Carolina Pastor Donnie Griggs’ church is active in the opioid fight. He suggests the following game plan:

- Research: Familiarize yourself with the opioid terminology and your area’s statistics. Learn about existing area resources. Get to know local first responders and hear their stories.

- Pray. Sincere, intentional prayer is crucial. Pray for all sides: the users, first responders, families and so on.

- Support: Assist local successful initiatives, whether Christian-based or not. Don’t create a competing version. “This fight is too big to be wasting bullets,” Griggs said.

- Lead: When God shows your church what need is missing in your community, fill that void. Maybe that means helping people with the financial burden of rehab or handling the funeral flower arrangement as a family buries a loved one who overdosed.

- Bottom line: “This is our problem,” Griggs said. “It’s every single Christian’s problem. Who else is going to give them the Gospel? Who else is going to love them like Jesus loves them if it’s not us?”

A 90-day prison rehabilitation wasn’t the answer; he relapsed 10 hours after he was discharged and soon was back in prison. There, he picked up a book that talked about the healing power of God. Jenkins scoffed and practically dared God from his jail cell, saying “God, if You’re real, heal me.”

Jenkins couldn’t explain it, but something changed. His resolve felt unique. He no longer craved needles. He even called his dad, told him where his drugs were stashed so he could destroy them. He felt healed, and maybe a little victorious—at first.

“Being sober and clean was fun for a little while,” Jenkins said. “God healed me of that, but I wasn’t serving Him. It was right when I got to the end, that day, it was like He intervened.”

A Concert, a Living Room & a New Life

Jenkins felt like his end was near. Sobriety had been a total letdown. For two years he had struggled to find any joy or any purpose in it, so he decided to head to Wilmington, North Carolina, and hustle up a shot of heroin. He realized injecting the powerful opiate would probably kill him because his drug-free body couldn’t tolerate it.

He was OK with that.

He woke up early that Sunday morning and started driving North Carolina Highway 24 south toward Wilmington. He knew this road well as he used to panhandle his way to the port city and back just to get his daily heroin fix. But his final destination was marred by an invitation.

The night before, he had taken his kids to a Christian concert, where some guys he knew invited him to their start-up church. You should join us, they urged him. Come as you are.

Jenkins agreed, but had zero intention of going. After all, he had a plan to execute.

But NC-24 took him right past this so-called church. Maybe he could just drive by and check it out.

When he pulled into the neighborhood, he said the guys saw him. They excitedly welcomed him with open arms.

“We said, ‘Hey man, what’s up? Cool you came.’ You could tell he wasn’t comfortable, but neither were we. We didn’t know what we were doing,” said Matt Barts, who owned the house where the church started.

It was overwhelming for Jenkins. He had been in plenty of living rooms playing guitar, but never without beer. And it was just weird when everybody but Pastor Griggs sat down. They didn’t think he was listening, but Jenkins remembers Griggs preaching from Colossians on the pre-eminence of God.

“I think the preaching resonated a little bit, but more than anything just the people really seemed like they freaking loved you,” Jenkins said. “I couldn’t believe it, dude.

“For them to mix in the truth with the love and just make much of Jesus is the key. I think that was because they never heaped any burdens on me, man. I would go home and be like there’s no way these guys like me like this. There’s no way they love me like a brother.”

But their actions showed otherwise. These guys didn’t let him languish. They followed up one simple invitation—hey, why don’t you come to our church?—with even more calls and texts. When he didn’t show up for church one Sunday, they were at his house 30 minutes afterward to check on him.

The authenticity pierced his heart.

They became his community, and they still are. When he had surgery earlier this year, they held him accountable to the pain prescription and even supported him as he stopped using suboxone strips—a small film taken orally to ease users out of opioid dependence. He’s been completely clean since then.

And Jenkins pressed in along the way, too. Giving up his old life meant giving up old friends, but to be honest, Jenkins said sadly, many of them had died.

Jenkins in 2018 isn’t just sober. He’s a new person who wakes up every morning thanking God, thinking “Wow. This is my life.” He runs his own business. He leads a Bible study with his wife. And he can’t stop talking about Jesus.

“It’s cool to see what God’s done in his life,” Barts said. “Gave him a purpose in life, and now he gets to tell his story. And it’s such a powerful story. It’s awesome, man.”

Billy Graham, Tattoos & Healing

Jenkins smiles when he says God is weaving him into His story, and he loves sharing his story. But he never could have anticipated sharing his testimony with hundreds at one time, which is exactly what he did during the Easter services at One Harbor, the once-living room church that now averages 1,600 people weekly at four sites. The come-as-you-are part has stayed intact. The Easter crowd wore everything from flat-billed ball caps and flip flops to neatly pressed shirts and slacks. A healthy dose of tattoos and facial hair were sprinkled throughout.

Pastor Griggs, born and raised in the North Carolina beach community of Morehead City, has a long beard, and his button-down, short-sleeved shirt didn’t even come close to covering up his tattoos. The crowd laughed when he assured everybody he was dressed up. He made everybody smile again when he introduced Jenkins. Steer clear of this man, Griggs insisted, if you don’t want to hear about Jesus at the local hardware store.

“Jenkins’ like the Billy Graham of Lowe’s,” Griggs laughed. “If you see this guy in Lowe’s and you don’t want to be a Christian, you should run. He’ll corner you by the caulk and nails. He’ll get you straight.”

But the onstage question-and-answer between Griggs and Jenkins took a serious tone when Griggs reflected on the fact that Jenkins had planned to end his life. Griggs pondered aloud if Jenkins had advice for anybody listening who might be struggling with addiction, or even sobriety for that matter.

Jenkins initially responded by congratulating anybody who didn’t have it all together. When he reached the end of himself, he said, is when God was able to do something.

“You have to persevere and fix your eyes on Jesus and not look away,” Jenkins said. “And trust He is who He says He is. And, again, the guys around me just pointed me back to Jesus every single time.”

Sitting in the congregation at One Harbor, Jeanette could barely keep it together. The mother of two had watched drugs rip her life apart. She had lost everything, and was facing the possibility of more prison time for drug-related charges. The real reason she was there on Easter Sunday was because her friend Rachel invited her. Jeannette said she experienced the peace of Christ during a prior prison sentence. She wanted that again.

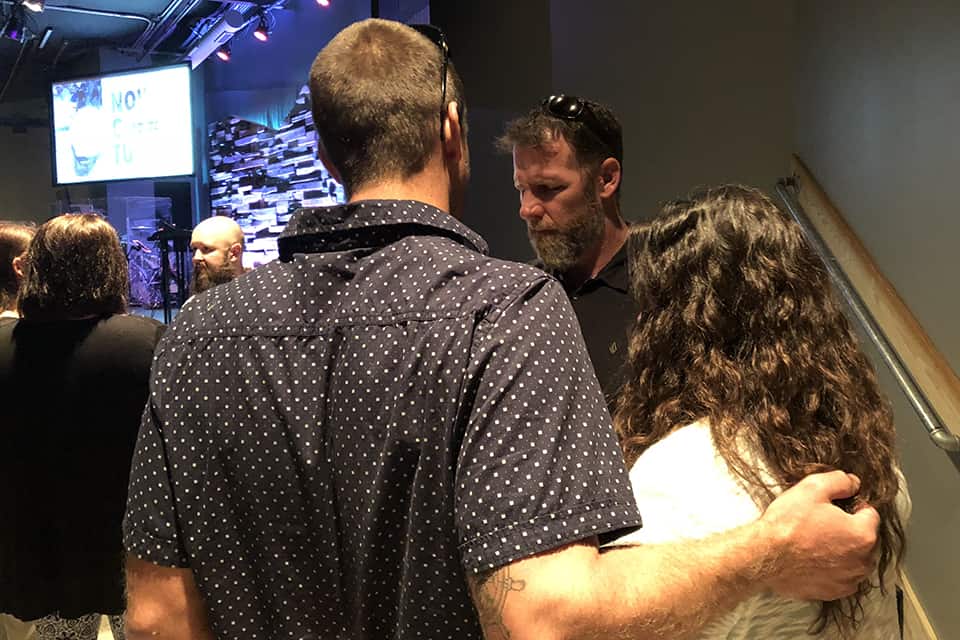

As Jenkins shared his story, she couldn’t stop the tears racing down her face. Rachel put her arm around her.

At the conclusion of the service, Jeannette couldn’t get to the front fast enough to talk with Jenkins and Griggs, whose own brother currently is serving time after decades of heroin use. She prayed with them and rededicated her life to Jesus Christ.

“Blind faith is a really hard thing to grasp,” she said. “But in my situation, I feel in my heart blind faith is what I need.”

Jeannette wasn’t the only one impacted. More than 2,000 people attended worship services on Sunday at One Harbor and its satellite campuses, and at the main Morehead City campus alone, many people came forward after each of the three services. Some wanted prayer for family, some wanted help for themselves. Others who weren’t ready to come forward issued their cry for help via contact cards offered by the church. One man, who just happened to be visiting from three hours west, said he was struggling big time. Jenkins texted the young man his number. “I’m on your team now,” Jenkins told him.

“You had the whole spectrum in the room. People who never used, people who got high this morning. People who it’s their job to go help [those who overdose],” Griggs said. “From 14 years old all the way to Grandma. Communities are being ravaged by this, and I think it’s on the church to do something.

“This is our problem. It’s every single Christian’s problem. Who else is going to give them the Gospel? Who else is going to love them like Jesus loves them if it’s not us?”

Give To Where Most Needed